Ten Boom starts her chronological autobiography with an out-of-time description of her happy life in Haarlem. “Childhood scenes rushed back at me out of the night, strangely close and urgent. Today I know that such memories are the key not to the past, but to the future” (ten Boom, 22). She continues, “…certain moments from long ago stood out in focus against the blur of years. Oddly sharp and near they were, as though they were not yet finished, as though they had something more to say” (ten Boom, 22). The reflexive attitude that ten Boom takes while recalling the horrific experiences entrusted to her autobiography may be startling to modern readers, and while she openly professes to human temptations, the author strives to show her readers what—more aptly, who—was her rock, fortress, and deliverer (Ps 18:2). Beginning her narrative with this complete trust in God sets the tone for the rest of her book. The reader, after being drawn in with the domestic cheerfulness pre-concentration camp, is shown the steady rock that will anchor ten Boom and companions through the rest of the book.

Her profound faith is what reveals the mysterious “hiding place”, which was not fully to be found neither in nooks nor crannies that would physically conceal sheltered Jews. Instead, ten Boom explains: “[God’s] will is our hiding place. Lord Jesus, keep me in Your will! Don’t let me go mad by poking about outside it…” (ten Boom, 154; brackets added). Taken out of context, the author’s words make no human sense—how can a logical person trust in a God that let the “apple of His eye” be taken away (ten Boom, 58)? Yet ten Boom presses her point. “I know that the experiences of our lives, when we let God use them, become the mysterious and perfect preparation for the work He will give us to do. I didn’t know that then—nor, indeed, that there was any new future to prepare for… There are no “ifs” in God’s kingdom.” (ten Boom, 22, 154).

However certain ten Boom’s mind was during publication, she hides nothing of her flawed human nature. The journey to complete dependence on God alone was a journey as easy as the train from Scheveningen to Vught (ten Boom, 122-123). Nonetheless, it was not without its highs accompanying its lows. A more prominent mentor was her father. While on one of their weekly trips to Amsterdam during her younger years, ten Boom asked her father an innocent question: “Father, what is sexsin?” (ten Boom, 29) Her father, instead of blustering or putting down her query, asked her to lift a suitcase filled with tools. When she protested that it was too heavy, her father replied with the sad, “…it would be a pretty poor father who would ask his little girl to carry such a load. It’s the same way, Corrie, with knowledge…For now you must trust me to carry it for you…” (ten Boom, 29). With the trouble taken off her shoulders, the young ten Boom was “wonderfully at peace” (ten Boom, 29). The trust that the author puts in her human father allows the readers to contemplate the trust in her heavenly Father.

Ten Boom did not limit her glimpses of heaven only to other people, but saw Divine Providence in every encounter, even with the smallest of creatures. In her solitary confinement cell at Scheveningen, ten Boom sheltered a colony of ants who lived in a crack near the base of the wall. As time passed, she developed a relationship with them, but was disappointed when they failed to emerge during a moment of her duress. Ten Boom’s breakthrough occurred when she realized God’s guiding hand even in perceived abandonment. “[The ants] were staying safely hidden. And suddenly I realized that this too was a message… For I, too, had a hiding place when things were bad. Jesus was this place, the Rock cleft for me…” (ten Boom, 121; brackets added). Both trust and optimism through adversity were the defining traits in ten Boom’s growing interior life.

The path from self-sufficiency to utter dependance was blessed by God, but the pilgrimage was far from over. Temptations riddled her interior life, and ten Boom was careful not to portray herself as a condescending, “holier-than-thou” hypocrite. Instead, she always pressed upon her readers that it was God’s grace, His love that enabled her to carry out her vocation and not her own feeble strength. She writes on her imprisonment as “seemingly pointless suffering. Every day something else failed to make sense, something else grew too heavy…” (ten Boom, 136). Even her hiding place, “worship and teaching … had ceased to be real…” (ten Boom, 146). However, the remedy to her struggles was not to struggle more, pushing aside heavenly aid. On the contrary, when burdens were too much or when she was overcome with rage, she begged God to love for her (ten Boom, 162). She writes more on her spiritual breakthrough after meditating on the letters of St Paul: “The real sin I had been committing was not that of inching toward the center of a platoon because I was cold. The real sin lay in thinking that any power to help and transform came from me. Of course it was not my wholeness, but Christ’s that made the difference” (ten Boom, 148).

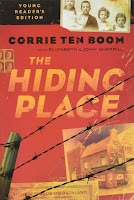

In The Hiding Place, ten Boom prescribes the one antidote to the human condition: acceptance of God’s grace. Taking it one step further, dwell not on human failures nor successes, but focus completely on God. St Peter walked on water while contemplating God, but failed to follow through in faith when he looked at the odds during the great storm (Mt 14:22). In her autobiography The Hiding Place, Corrie ten Boom discusses the true hiding place, her journey towards it, and the persecutions on her pilgrimage. In the 21st century, modern readers are more readily able to accept God’s will and God’s word without threat of persecution. What, then, is to stop modernity from following ten Boom’s example and “[keeping] eyes fixed on that bit of heaven…” (ten Boom,110; brackets added)?

WORKS CITED

Ten Boom, Corrie et al. The Hiding Place, E-book edition, Chosen Books, 2011, Accessed 29 Jan. 2021

The Holy Bible. Revised Standard Edition, Ignatius Press, 2005.

Comments

Post a Comment